Key Points

- Tariff impacts on consumer prices depend on “tariff pass-through,” and the pass-through rate varies according to the price sensitivity of import quantities and market structure.

- Inventory accumulation resulting from front-loaded exports, as well as margin compression at the wholesale and retail stages, are likely to suppress the short-term pass-through of tariff burdens to consumer prices.

- There are limits to absorbing tariff impacts through inventory adjustments or margin compression at the wholesale and retail levels, making it highly likely that consumer burdens will increase over the medium-to long-term.

Trump 2.0 Tariffs and the U.S. Consumer Prices

In 2025, the United States imposed additional tariffs—so-called “Trump 2.0 tariffs”—on a wide range of imported goods. In general, higher import costs resulting from tariffs raise the domestic prices of imported goods and can also spill over to competing domestically produced goods. As a result, tariffs can adversely affect U.S. consumers.

Figure 1 uses data provided by Cavallo et al. (2025) to show the daily movements in the consumer price indices for imported and domestically produced goods in the United States. Consumer prices for imported goods had been on a downward trend since October 2024. However, following the additional tariffs imposed on Canada, Mexico, and China in early March, as well as the tariffs imposed on April 5, often referred to as the so-called “Liberation Day” tariffs, prices turned upward. Prices of domestically produced goods exhibited similar movements, indicating that rising prices of imported goods exert upward pressure on competing domestic goods, as well as on domestic goods that use imported products as parts or intermediate inputs.

Nevertheless, despite the “Liberation Day” tariffs imposing a uniform 10 percent tariff on all countries—and additional country-specific tariffs on top of that—the increase in consumer prices for imported goods has remained limited to only around 2–3 percent compared with October 1, 2024. Therefore, Trump 2.0 tariffs did not result in a significant overall price increase. Who, then, is actually bearing the burden of the Trump 2.0 tariffs? To answer this question, it is essential to understand how tariff costs are transmitted to consumer prices.

Figure 1: U.S. Consumer Price Index (October 1, 2024 = 100)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data published by Cavallo et al.

Tariff Pass-Through

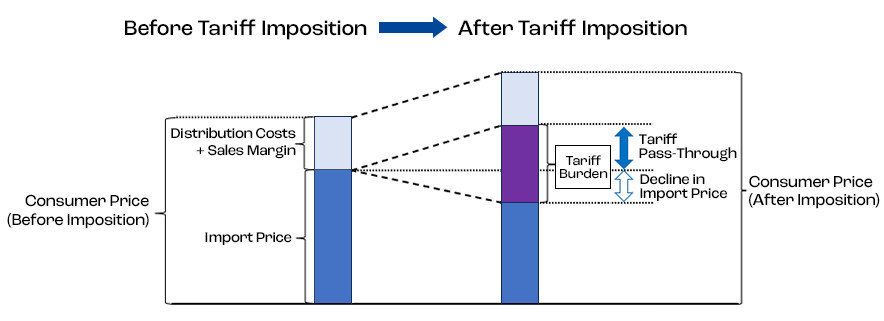

When considering who bears the burden of tariffs, the key concept is “tariff pass-through.” Tariff pass-through refers to the extent to which the increase in import costs caused by a tariff is passed on to the after-tax import price paid in the importing country. As shown in Figure 2, suppose that, prior to the imposition of tariffs, the consumer price of an imported good is determined by adding wholesale and retail margins and logistics costs to the import price. Starting from no tariffs, if the United States imposes a 10 percent tariff and the U.S. import price (i.e., the export price charged to the United States by foreign suppliers) falls by 4 percent, then the after-tax import price will rise by 6 percent. In this case, the tariff pass-through rate is 60 percent, meaning that 60 percent of the tariff burden is borne on the U.S. side, while the remaining 40 percent is borne by the exporting country. If wholesale margins and logistics costs remain unchanged after the tariff is imposed, then consumer prices for imported goods will also rise by 6 percent, and this increase will directly translate into a burden on U.S. consumers.

Figure 2: Tariff Pass-Through

Source: Created by the author

If the pass-through rate is 100 percent, the after-tax import price rises by the full amount of the tariff, placing a substantial burden on U.S. consumers. At the other extreme, a zero pass-through rate implies that exporters bear the entire tariff burden. Tariff pass-through is thus an important indicator for measuring how tariff burdens are divided between consumers in the importing country and exporters in the foreign countries.

No study has yet estimated the pass-through rate for the newly imposed Trump 2.0 tariffs. However, according to empirical analyses of the tariff increases imposed on China during the first Trump administration in 2018—specifically, the study by Amiti et al. (2019) and the study by Fajgelbaum et al. (2020)—the pass-through rate of those tariffs was reported to be close to 100 percent. Nevertheless, judging from recent movements in consumer price indices, the consumer burden of the new Trump tariffs appears to be relatively subdued at this point despite the high tariff rates that have been imposed. Below, I outline the factors that influence tariff pass-through and consider the reasons behind this pattern.

Factors Affecting Tariff Pass-Through

First, the fact that the Trump tariffs apply to a wide range of imported products may be influencing tariff pass-through. It is well known that tariff pass-through tends to be larger for goods whose import demand does not decline significantly, even when prices rise; that is, goods with low price elasticity of import demand. When demand reacts only weakly to price changes, firms can pass tariff costs on to consumers with less fear of losing their sales volume.

The price elasticity of import demand varies depending on the characteristics of imported products. For example, the more differentiated a product is—and the less substitutable it is with other products—the lower its price elasticity tends to be. During the 2018 U.S. tariff increases on China, many of the goods imported from China—such as footwear, furniture, and electrical equipment—were relatively differentiated products. This implies that price elasticity may have been low and that tariff pass-through may have been high. However, because the new Trump tariffs apply to a large number of items, including goods with high price elasticity, the overall pass-through rate may be relatively low. Indeed, reports by Cavallo, Llamas, and Vazquez indicate that while consumer prices for furniture and household goods rose substantially, price increases for food, which has many substitutes and is difficult to differentiate, were limited.

Second, a competitive market structure may be suppressing tariff pass-through, meaning that price increases are being constrained. In product categories where competition among firms is intense, exporting firms have incentives to keep their export prices unchanged and absorb tariff costs; raising their export prices alone would cause them to lose significant market shares to competitors. In other words, the more competitive the market and the lower the market concentration, the higher the price elasticity of import demand tends to be. Consequently, more competitive market structure leads to the smaller the tariff pass-through. Because the Trump 2.0 tariffs are broad and involve many countries, exporting firms would have strong incentives to keep pass-through low to maintain their market shares.

Third, the fact that Trump tariffs apply different tariff rates to different countries may also be suppressing tariff pass-through. High tariff rates substantially reduce exports from countries facing high rates, while exports from countries facing relatively low tariff rates decline less or may even increase. This reflects the so-called “trade diversion effect,” whereby demand shifts from high-tariff to low-tariff countries. If exporters relocate production to low-tariff countries, this indirect effect becomes even stronger. Consequently, the import-reducing effect of tariffs becomes limited, the effective burden of tariffs becomes smaller, and tariff pass-through is correspondingly suppressed.

Other Factors Suppressing Consumer Burdens

In addition to low tariff pass-through, the following factors may also be suppressing increases in consumer prices. First, inventory accumulation resulting from front-loaded exports and policy uncertainty also plays a role. High tariff rates were anticipated from the beginning of President Trump’s term, and the “Liberation Day” tariffs were not applied immediately but were accompanied by a 90-day pause period. These circumstances encouraged front-loaded exports from many countries. Because firms could supply goods from inventories accumulated prior to the tariff increases, part of the tariff burden could be avoided. In addition, since April, President Trump has frequently changed both tariff rates and implementation schedules. This may prompt exporting firms to avoid overreacting and instead adopt a wait-and-see approach. As a result, despite the imposition of Trump 2.0 tariffs, the supply of imported goods within the U.S. may not have declined significantly, helping restrain consumer price increases.

Furthermore, U.S. wholesalers and retailers that handle imported goods may absorb part of the tariff burden by reducing their own margins, which can also curb increases in consumer prices. Figure 2 illustrates a case in which wholesale margins remain constant after tariffs are imposed. However, in practice, domestic distributors may reduce their margin rates to avoid a decline in sales resulting from price increases. In such cases, even if tariff pass-through is high and after-tax import prices rise substantially, consumer price increases will be smaller to the extent that the distribution margins shrink.

In fact, according to research by Cavallo et al. (2021) analyzing the 2018 U.S. tariffs on China, although the pass-through rate at that time was close to 100 percent, retail prices did not rise as much as the tariff rate. This suggests that a significant portion of the tariff burden was absorbed by U.S. wholesalers, retailers, and other distributors. Similarly, research by Baek et al. (2021) using Japanese data confirmed that higher tariffs reduce wholesale margin rates. Even if the Trump 2.0 tariffs have not resulted in a burden on U.S. consumers, they have effectively imposed costs on U.S. firms.

As described above, numerous factors interact in determining tariff pass-through and the degree to which after-tax import prices move in tandem with consumer prices. For this reason, identifying the precise burden-sharing structure of the Trump 2.0 tariffs is not straightforward. A more detailed analysis, including the use of firm-level data, will be required going forward.

Outlook

Forecasting the future impact of the Trump 2.0 tariffs on U.S. consumer prices is not easy, but it is possible to outline prospects by considering the factors related to tariff pass-through and the transmission of tariff burdens to consumer prices discussed above.

First, the effects of inventory adjustments resulting from front-loaded exports will diminish as inventories are depleted. In addition, although competitive market conditions have made it difficult for exporting firms to pass tariff costs on to export prices, this situation could change if exporters enhance product quality or differentiation, or if more exporters withdraw from the U.S. market because of the tariff burden. Such developments could ease market competition, thereby reducing the price elasticity of import demand and increasing tariff pass-through. Moreover, U.S. wholesalers and retailers that have been absorbing tariff burdens by compressing margins also face limits to this strategy. In the medium to long term, such efforts within the distribution stage are not sustainable, and tariff burdens will gradually be passed on to consumer prices.

Although trade diversion effects and shifts in production locations induced by differences in tariff rates across countries may continue to suppress tariff pass-through, the overall effect on suppressing price increases is likely to be limited, given that additional tariffs have been broadly imposed as a baseline. Moving production to the U.S. can help firms avoid tariffs, but producing in the U.S. itself is a cost-increasing factor; therefore, it does not remove the upward pressure on U.S. consumer prices.

Based on the above, although increases in U.S. consumer prices remain relatively moderate at present, tariff pass-through is expected to increase further over time, gradually exerting upward pressure on prices and ultimately increasing the burden on U.S. consumers. In fact, President Trump—who had repeatedly argued that exporting countries bear the tariff burden—has recently begun making statements acknowledging that tariffs are being borne by the American public.

(c)ZUMA Press/amanaimages