Key Points

- The “National Security Strategy” (hereafter, “NSS2025”) rejects the post–Cold War self-image of the United States as a ‘liberal’ hegemon while reaffirming its determination to remain the world’s most powerful great power.

- While carefully avoiding explicit references to China—particularly in the defense context—NSS2025 articulates its resolve to “deny” any attempt at regional domination and to maintain the balance of forces along the “First Island Chain.”

- The Trump administration’s concept of “burden sharing” should be understood not only in bilateral U.S.–Japan terms, but within a broader network involving Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, and European allies.

- U.S. allies including Japan see this network not only as a burden-sharing platform but also as a broader instrument to address many other issues regarding the transition of the international order.

Historical Perspective and Worldview in the National Security Strategy

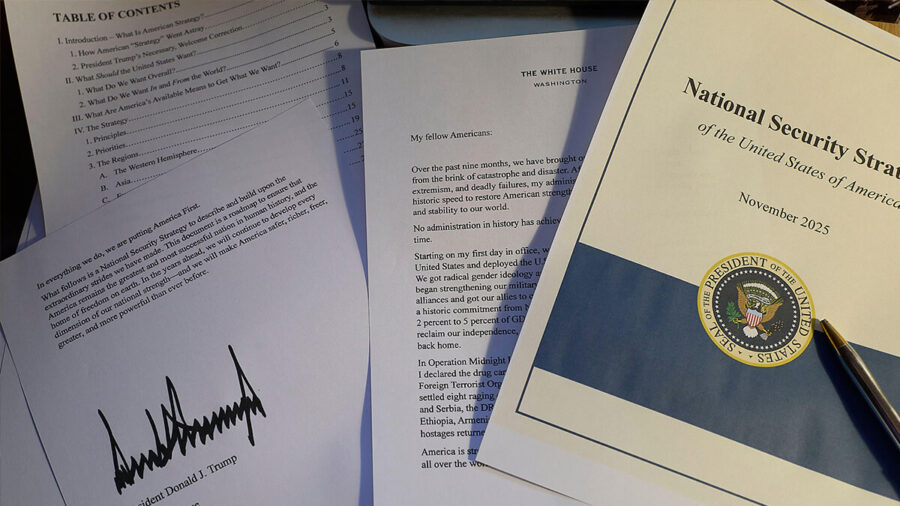

Released on December 4, 2025, the Trump administration’s “National Security Strategy” (hereafter, “NSS2025”) is built around a striking historical narrative that directly challenges the United States’ traditional self-image. The document sharply criticizes successive post–Cold War administrations for pursuing “permanent American domination of the entire world,” arguing that efforts to sustain and expand international institutions and involvement in conflicts “peripheral or irrelevant” to U.S. interests eroded the foundations of its own power—namely, the middle class and the industrial base. For readers less familiar with international relations theory, this worldview amounts to a direct repudiation of the United States as a “liberal” hegemon. The (neo)liberal theoretical concept, articulated by G. John Ikenberry, describes U.S. leadership as rooted in the creation and maintenance of international institutions such as the IMF and WTO, alongside the restrained use of its dominant military power in careful consideration of other participating states’ interests in the hegemonic order.

In this theoretical view, democratic values are cast, both implicitly and explicitly, as a key foundation of U.S. liberal approaches towards international order—a claim which is, in many ways, aligned with the post-Cold War history of Washington’s foreign policy thinking that emphasised the promotion of liberal democratic values across the globe. NSS2025, however, asserts that these approaches must be discarded in order to advance what it conceives of U.S. national interests under the banner of “America First.”

That said, this historical critique does not necessarily amount to a wholesale rejection of every long-standing U.S. strategic principle—at least as reflected in the document itself. At the outset, NSS2025 declares that the strategy is necessary to ensure that the United States remains “the most powerful, prosperous, dynamic, and successful nation in the world for decades to come.” The strategy further asserts that peace is sustained through the U.S. power, enabling global economic prosperity, which in turn reinforces U.S. strength in a virtuous cycle.

In this sense, NSS2025 quietly reaffirms a core worldview that the Trump administration seems to share with many past administrations: the exceptionalism that the preservation of U.S. status as the most powerful great power in the world contributes to international peace and prosperity. What distinguishes the document, however, is its conviction that abandoning the aforementioned liberal hegemonic approach would rather enhance such a crucial foundation of the U.S. power, in its view, for the peace and prosperity of the world.

Two Strategic Pillars in the Indo-Pacific

The historical perspective and worldview embedded in NSS2025 are operationalized in the Indo-Pacific through two key policy pillars.

First, NSS2025 explicitly states its determination to prevent the “global and ,in some cases, even regional domination of others” and to deny any attempt to seize Taiwan. Particularly notable is its clear rejection of any unfavorable shift “in the balance of forces” along the First Island Chain. While the document avoids explicitly naming China, the intent to deny regional domination is unmistakable. The strategy further outlines an ambitious vision to expand U.S. GDP from roughly $30 trillion to $40 trillion by the 2030s by reshaping economic relations with China into a “truly mutually beneficial” arrangement—an ambition that indicates Washington’s sense of competition with China. (Despite these words, as Ryo Sahashi notes, U.S.– China negotiations may not necessarily unfold in ways consistently favorable to the United States.)

Second, NSS2025 underscores the importance of “burden sharing” with allies in keeping China’s strength in check. This emphasis extends beyond bilateral alliances to encompass a broader network of partners, including Japan, Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, and European allies. In this context, the defense-spending commitment agreed at the Hague Summit of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)—setting core defense expenditures at 3.5 percent of GDP and total related spending at 5 percent—has been framed as a “new global standard.” The United States has made clear that it will support allies willing to assume greater responsibility in their own regions, explicitly highlighting Japan and South Korea.

Within Japan, NSS2025 is commonly interpreted as signaling U.S. expectations—and pressure—for Tokyo to raise defense spending to 3.5 percent of GDP and deepen burden-sharing within the bilateral alliance. While understandable, this interpretation remains incomplete in two important respects.

First, debates over numerical spending targets, though important, capture only part of the picture. This is a “longstanding yet recurring theme” in the U.S.–Japan alliance. During the late Cold War, for example, the Carter administration pressed Japan to increase defense spending, prompting Tokyo to advance the concept of “comprehensive security” and to emphasize broader responsibility-sharing beyond budgetary metrics. Today, as Japan reviews its so-called “three security documents,” including how defense expenditures are treated, numerical debates should be assessed within a wider context that also overarches questions on the evolving international order, strategic objectives for the alliance, respective defense strategies, and force posture and structure.

Second—and more importantly—framing burden sharing solely within a bilateral U.S.–Japan context increasingly diverges from the strategic realities facing Japan and other Indo-Pacific partners. NSS2025 itself invokes the concept of a “burden sharing network,” emphasizing the strengthening of allied and partner efforts along the First Island Chain and the interlinkage of maritime security challenges across the region. Yet such interlinkages are not destined to become practical automatically. Without deliberate efforts to foster mutual understanding, coordination, and synergy, broader network-based cooperation remains difficult to implement.

Taken together, the “burdens” and “responsibilities” borne by U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific, including Japan, should be analysed not only within bilateral frameworks—such as U.S.–Japan, U.S.–Australia, U.S.–Philippines, or U.S.–South Korea relations—but as part of a broader concept centered on (but not limited to) how to strengthen and expand a “burden-sharing network” composed of multiple U.S. allies and partners. While policy debates and academic research on the nature of this network have already begun to advance in both the United States and Japan, these discussions should continue to evolve in step with rapidly changing empirical realities.

Burden-Sharing Network: Progress, Issues and Questions

Obviously, “network” cannot simply be reduced to bilateral U.S.–Japan ties. It also entails broader cooperation with third parties—including, but not limited to, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines—because such arrangements, in Washington’s views, may support U.S. strategy and, therefore, form part of the “burdens” and “responsibilities” that allies like Japan shoulder. Furthermore, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines’ efforts to deepen ties with each other can be treated, from the U.S. perspective, as elements of this broader network insofar as they ultimately reinforce the U.S.–Japan alliance and Washington’s strategy even if neither of Tokyo nor Washington is a direct participant in every cooperative activity.

A crucial policy and analytical issue that emanates from NSS2025 is that the U.S. and its allies in the Indo-Pacific do not necessarily see the nature of this evolving network of cooperation in exactly the same lights. The following is the preliminary outline of where they appear to have more convergence and potential divergence.

<Broad convergence: Deepening Japan–Australia–Philippines Cooperation>

The idea of interlinking maritime security challenges along the First Island Chain, as NSS2025 highlights, aligns with recent trends in Indo-Pacific minilateralism in which the Japan–Australia partnership has been at the forefront. Following the 2022 Japan–Australia Joint Declaration on Security Cooperation, both countries have advanced discussions on Scope, Objectives, and Forms (SOF) including responses to contingencies. Although the details of these discussions have not been made public, they nonetheless point to a clear effort by Japan and Australia—despite their geographical distance—to clarify and expand the strategic synergies between their respective security strategies. For example, Australia has been in the process of operationalising its 2024 National Defence Strategy to “deny” potential hostile activities across its “near region,” stretching from the eastern Indian Ocean through maritime Southeast Asia to the South Pacific. By so doing, Canberra aims to prevent any unfriendly powers from expanding from the North down to its homeland in the South. Seen from Canberra’s such strategic view, Japan’s efforts to defend itself and to prevent unilateral changes to the status quo in its proximate seas and airspace contribute to Australia’s strategic objectives by at least impeding penetrations and expansion by potential adversaries into areas closer to Australian continent. In the meantime, Australia’s denial strategy helps maintain the stable use of sea lanes vital to Japan and thereby supports U.S. force posture in the region—illustrating interactive strategic synergies that their cooperation is designed to expand.

Japan and Australia have also expanded cooperation with the Philippines, contributing to the development of the Japan–U.S.–Australia–Philippines framework, commonly referred to as “the Squad.” While observers often give credits to U.S. policy in promoting this particular quadrilateral framework, the respective and coordinated initiatives by Japan, Australia, and the Philippines have been equally significant. For example, the Philippines has increasingly recognized the strategic importance of its northern maritime areas, including the East China Sea—a shift in perception to which Japan has long worked to promote. Testifying this crucial expansion of their geopolitical gaze is a series of joint statements issued by “the Squad” which consistently emphasize cooperation spanning both the South and East China Seas.

Beyond rhetoric, “the Squad” is advancing concrete initiatives to enhance Philippine maritime domain awareness (surveillance and monitoring capability) and information-sharing among the four countries. This includes Japan’s transfer of air surveillance radar systems to the Philippines. According to research conducted by the Sasakawa Peace Foundation, radar installations in northern Luzon contribute not only to South China Sea monitoring but also to enhanced domain awareness in the East China Sea and greater overall system redundancy. These developments are rapidly becoming concrete, not just rhetorical, elements of what the U.S. considers as burden-sharing network.

<Potential divergence: The Korean Peninsula and Europe>

At the same time, apparent gaps exist between NSS2025 and the perspectives of Indo-Pacific partners. One such gap concerns the Korean Peninsula.

South Korea has increasingly emphasized the importance of peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait and has openly opposed “attempts to change the status quo” in the South China Sea. Cooperation with the Philippines has advanced, as evidenced by South Korea’s participation in the Kamandag joint exercise (with Japan also participating) and the transfer of naval vessels to the Philippine Navy.

Nevertheless, security on the Korean Peninsula remains South Korea’s foremost priority. Given their geographical proximity, security on the Korean Peninsula and maritime challenges along the First Island Chain are deeply interconnected. Yet, NSS2025 makes no reference to the Korean Peninsula or North Korea, creating a perceptible gap with Japan’s view on the partnership with Korea (and the Japan-Korea-U.S. trilateral) as a vehicle to advance both Korean peninsular and broader Indo-Pacific security together. This potential divergence suggests that the interlinkages between peninsular and broader regional security issues may be a crucial and increasingly critical subject among Japan, Korea and the U.S..

Another notable omission in NSS2025 concerns Europe’s role in the Indo-Pacific. While the document discusses the Western Hemisphere, Asia, and Europe in separate compartments, it devotes little attention to their interconnections. This omission suggests a potential gap between the strategy and the approaches of allies such as Japan, Australia, South Korea, and the Philippines, all of which place growing emphasis on Europe’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific.

In 2025, several European countries—most notably the United Kingdom and France—carried out successive carrier strike group deployments in the Indo-Pacific. The United Kingdom has already stationed nuclear-powered attack submarines in Perth under the AUKUS framework, with rotational deployments planned from 2027 onward. France has supported Philippine Coast Guard capacity-building and participated alongside Japan and the United States in joint maritime activities in the South China Sea.

The joint statement issued at the “G7 Defense Ministers’ Meeting” in October 2024 described the Indo-Pacific as the “center of global growth, geopolitical development, and military balance,” underscoring a significant shift in European strategic perceptions (while it is needless to note that their home theatre remains their absolute priority).

Looking Ahead

Taken together, these considerations suggest that the nature of evolving network among the U.S., its allies and even countries beyond is an increasingly critical policy and analytical subject to explore. Here differences in how such a network should be conceptualized and operationalized are inevitable and natural among Japan, the United States, allies and many other partners given their unique historical and geopolitical profiles

The bottom line is that Japan and other U.S. allies do not view their expanding cooperative networks simply through the narrow lens of “burden sharing.” Instead, their network of cooperation is often expected to serve as a platform for addressing a broader set of questions amid the historic transition of international order on top of their continuing alliance with the United States.

From this vantage point, for example, the questions on the potential return of bloc politics, the roles of non-great powers and/or the concept of a U.S.–China “G2”—assume greater salience as key subjects for their discussions and/or cooperation. Equally important are discussions surrounding regional economic frameworks not addressed in this article, as well as the long-term modalities of engagement with nonaligned countries, including India and Southeast Asian states. The emerging network of cooperation is, therefore, a crucial theme for both policy debate and scholarly inquiry, not only between Japan and the United States, but also among Japan and its partners across the region and the world.

(c)Almay/Amana images